As is understood, a trademark is a mark that helps identify the origin or source of goods and services with the help of a uniquely differentiable graphical representation, which may be manifested in the form of a sign, symbol, word, label, or even a combination of several elements put all together. Therefore, it aims to differentiate the goods and services of one from that of another in today’s era of a global market, eliminating the risk of confusion and losses accompanied by such risks.

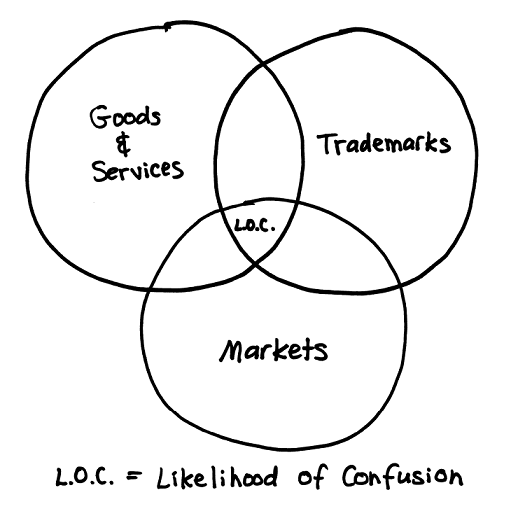

When a trademark is scrutinized by a Trademark Office or when it is underdetermination for possible infringement, it is often subjected to the test of “likelihood of confusion.” Hence, in such a scenario, there is a clear division of parties and their interest. The party that first adopts a mark by using it in the market is termed as the Senior or First User, and the one that adopts a similar mark later than that of the Senior User comes to be identified as the Junior User.

The Initial Interest Theory: The Consumer Perspective

The main aim of a consumer while seeking a particular good or service is finding a distinguished quality and preferred price. Due to the plethora of options available in the physical market and the digital space, there has been an unprecedented growth in the number of counterfeit goods, which misappropriate trademarks resulting in consumer confusion. The initial interest theory is often taken into consideration by judges and courts to understand the psychology of consumers when contemplating similarities between trademarks by considering the imperfect recollection memory of a consumer, the behavioral pattern of a consumer while deciding what to purchase, etc. This theory is further bifurcated into two crucial theories, which can be understood in the next segment.

The Forward Confusion Theory

In infringement cases, it is often witnessed that there is a small entity, which is a new entrant, wrongfully posing as another massive entity to take advantage of the established reputation and goodwill by simply creating consumer confusion while misrepresenting its trademark. A deliberate attempt to create confusion is made to suggest an affinity with a Senior User, which harms the commercial and moral interest of the Senior User as well as that of the consuming audience since such goods often under-deliver and underperform on the scale of quality and quantity.

The Reverse Confusion Theory

The very opposite of the forward theory of confusion is the theory of reverse confusion. In such cases, a consumer fails to distinguish between goods and services of the Junior and Senior User of a mark and associates the underlying products to be originating from the Junior User on account of a robust marketing and a saturated market. The same leads to a lack of recognition of the Senior User causing potential harm. It can be somewhat mindboggling.

The theory came much into the picture in Big O Tire Dealers, Inc. vs. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., wherein it was held that “the second use of a trademark is actionable if it simply creates a likelihood of confusion about the source of the first user’s products.”

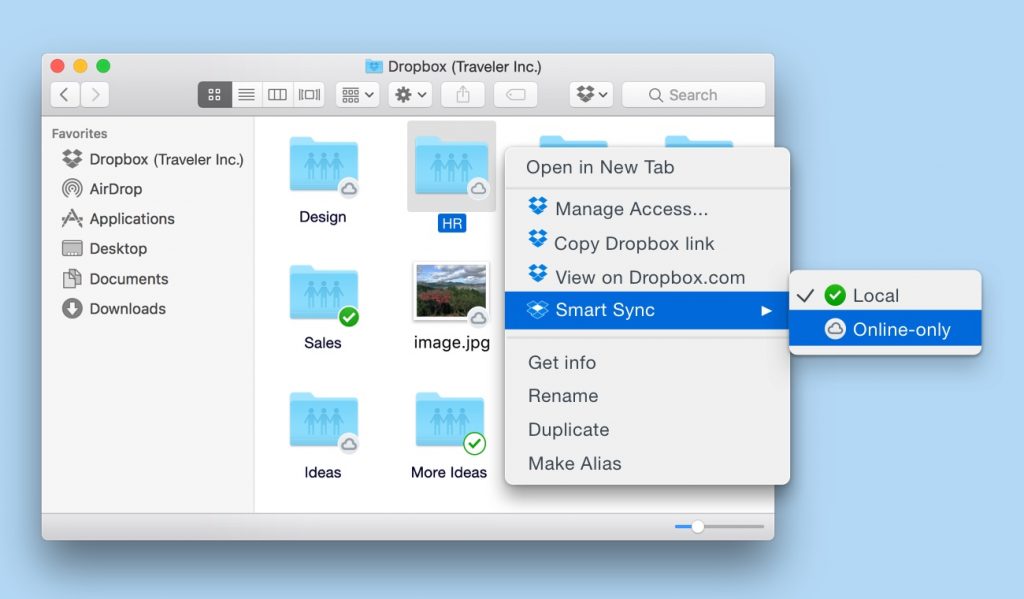

Last year, the case of Ironhawk Technologies, Inc. v. Dropbox, Inc. (decided on April 20, 2021) came forth to the Ninth Circuit, where the theory was under much speculation. Herein, the plaintiff was a computer software developer of ‘SmartSync’ developed in 2004, utilizing compression technology to enable an efficient transfer of data, particularly in bandwidth-challenged environments. Its products were sold majorly to the US Navy. Dropbox brought cloud storage software to be made accessible throughout the world. Its software featured ‘Smart Sync’ while enabling a user to see and access files in his Dropbox cloud storage account without using up any of the user’s hard drive storage. Furthermore, Dropbox launched its Smart Sync feature in 2017 and was previously aware of Ironhawk’s SmartSync mark. Ironhawk brought a case against Dropbox for the violations of the Lanham Act alleging Trademark Infringement and unfair competition, pleading that Dropbox’s use of the name ‘Smart Sync’ intentionally infringed upon Ironhawk’s ‘SmartSync’ trademark. At an earlier event, Dropbox had attempted to acquire Ironhawk, evidencing recognition of the competitor. The Ninth Circuit deduced in favor of Ironhawk since it stated that there was a likelihood of reverse confusion. However, when the case went for further trial, Judge Wallace Tashima found the judgment of the Ninth Court to be erroneous since Ironhawk only had a “sophisticated audience,” unlike Dropbox, catering to a much wider audience. Therefore, it was found that it was unlikely that reverse confusion may have occurred.

Conclusion: Points of Consideration

There is no rigid test laid down to deduce the application of the theory of reverse confusion; however, courts have developed a case-bade modified multi-factor test. The underlying factors shall be taken into consideration when deciding on reverse confusion:

- The conceptual strength of the mark – The courts evaluate whether the mark is suggestive, arbitrary, fanciful, or descriptive. The more strength it carries, the more distinctive it is. Therefore, if a mark is more distinctive, there is more likelihood of confusion since the attempt to imitate becomes rather apparent.

- The similarity between the two marks: The court will determine the visual, ocular, and phonetic difference between the marks while drawing a comparison of the totality of the mark.

- Possibility of actual confusion: The likelihood of confusion will be assessed considering the adjoining factors like channels of trade and commerce, the consuming audience, the quality and quantity of the product, etc.

- The intention of the infringer

Even though the courts are bringing to consider such theories of confusion, it will be interesting to observe how they would grant awards supporting the theory since it may land a chilling effect by over-compensating the Junior User.