Websites and mobile applications have come to play a pivotal role in consumer engagement and the growth of a brand in recent times. The use of digital technology has transformed the way we shop and connect to retailers. In this scenario, a website or an application assumes significant responsibility to make memorable experiences to which consumers like to return, time and again. Therefore, retailers, stakeholders, investors, and service providers often turn to Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) to protect their creativity. However, the Trade Dress Law has also ushered attention apart from seeking trademark and Copyright Protection due to legal limitations

Trademarks, Copyright, or Trade Dress: The Better Alternative?

Trade Dress Protection, initially conceptualized and found in the Lanham Act (USA), essentially referred to the design or the packaging of a product, which initially was limited to the distinctive shape, size, or the overall appearance of the product. However, the nascent law has evolved to include other aspects that can be protected, for example, the atmosphere of a restaurant, the layout of a store, etc.

As mentioned above, there are other alternatives to protecting and safeguarding a website via copyright and trademarks. Trade dress differs from Trademark Protection since where a trademark protects an individual aspect of a brand like a word, symbol, device, peculiar color, etc., a trade dress safeguards “the totality of the elements and the overall impression made by the identified elements.” It may not be the best way to safeguard a website since a trademark protects the trade name or a symbol associated with the brand and not any additional aspects, like the website or mobile application or store layouts.

When it comes to copyright protection, the problem is that the law on copyright protects only the creative content available on the website or app. For instance, the blog or the manual of instruction or reviews or an interview with the user or retailer regarding a product or original photographs can be copyrighted to prevent illicit copying. The same cannot be extended to the look and feel of the website.

Deciphering the ‘Look and Feel‘ of a Website

The instances of seeking protection for a website or a mobile app have recently increased after the courts have moved to agree to such extension of the law on trade dress; however, the bar is relatively high to pursue such a course of action.

The first suit of such a kind was witnessed in 2007 in Blue Nile, Inc. v. Ice.com, Inc., where a District Court in the USA deliberated on the applicability of the trade dress law on a website. The Court concluded that the ‘look’ in the ‘Look and Feel’ of a website means the design and layout of a website inclusive of the colors, layouts, type cases, shapes utilized on the website, and ‘feel’ refers to the interface design and the aspect of how a user interacts and connects with the functionality of a website, thereby including elements like the buttons, drop-down lists, boxes, menus, and hyperlinks available on the website. In Conference Achieves, Inc., the Court further elaborated on the issue.

The standpoint on the issue is instead nascent in India as well. In The Himalaya Drug Company v. Summit, the Delhi Court adjudicated in favor of the Plaintiff to restrain the Defendants from utilizing the database on the details of medicinal herbs available on the Plaintiff’s website. The Court held, “The Plaintiff has also been able to demonstrate that the Defendants have attempted to pass off their herbal database as and for that of the Plaintiff’s and have also violated the ‘trade dress’ rights that exist in respect of the Plaintiff’s herbal database. The reason is that the Plaintiff’s herbal database is unique, and therefore, any similar herbal database that appears on a different website is bound to create confusion by causing a consumer to associate the website with that of the Plaintiff. If any further evidence of the Defendants’ conduct in attempting to pass off their website as that of the Plaintiff were needed, it is clear from Exhibit P15 wherein the metatag of the source code of the Defendants’ website includes the Plaintiff’s trademark Himalaya Drug Co.” Hence, protection as a trade dress was afforded to the Plaintiff on account of unique and distinctive features.

The Bump on the Road

Since most enterprises have a website and purport to make sales, online and offline, the standard of obtaining protection as a trade dress is rather more stringent. The same is to prevent unfair trade practices or unfair monopolies in favor of a single proprietor. Therefore where a cause of action for the infringement of a trade dress is pursued, the party must:

- Define what constitutes a trade dress;

- Establish that the claimed trade dress is not functional in nature;

- Establish that the said trade dress is either inherently distinctive, or conversely, has acquired secondary meaning, which indicates the origin of the goods or services; and

- Demonstrate that there exists a likelihood of confusion between the allegedly infringing product and the existing trade dress.

Deciphering each of these elements in the prong test mentioned above, let us first consider the need to define the particular trade dress. It is imperative to identify all the small elements at first and then figure out how these small elements combine to form a comprehensive trade dress. Therefore, a vague statement like the “website layout is different” or “distinctive” or “widely recognized” or “likely to create confusion” may not suffice in the court of law. Concrete measures to establish distinctiveness based on elements and interaction of such elements in a website is necessary. Consider the case of Parker Waichman LLP v. Gilman Law LLP, where the Plaintiff enlisted not all but a few peculiar features like the particular color, layout, and interactive buttons that constituted a part of their trade dress. Since the Plaintiff failed to synthesize and depict how such elements interacted with one another, the Plaintiff’s cause of action and his allegations were held not sustainable. Contrary to the same, in Express Lien, Inc. v. Nationwide Notice, Inc., the Plaintiff identified the unique features of the website while synthesizing all the enlisted elements.

Secondly, to qualify as a trade dress, the features should not be functional in nature and should not affect the cost or quality of the product. The aspect of functionality has to be looked at in totality and not while dissecting each element. Therefore, where multiple elements form one complete visual, the fact that an individual element may be functional should not result in one considering that the complete trade dress is functional. For example, in the Fair Wind Sailing v. Dempster case, the Plaintiff identified “the choice to employ catamaran vessels solely, its unique teaching curriculum, and student testimonials” as elements of the website for their sailing school. The Court held all of these features to be functional in nature since they added to their cost and the demand for their service.

Thirdly, the trade dress should be distinctive in nature due to an acquired secondary meaning. ‘Secondary Meaning’ means that the ‘look and feel’ of the website is such that there is a mental association with the website to the extent that when consumers or potential consumers look at the website, they can trace back its source. Various factors contribute to this prong, such as the extent and manner of advertising, the graph of sales, the media attention gathered by the product, and the length of use, to name a few. It is one of the most arduous elements to establish and thus forms a decisive factor in infringement cases.

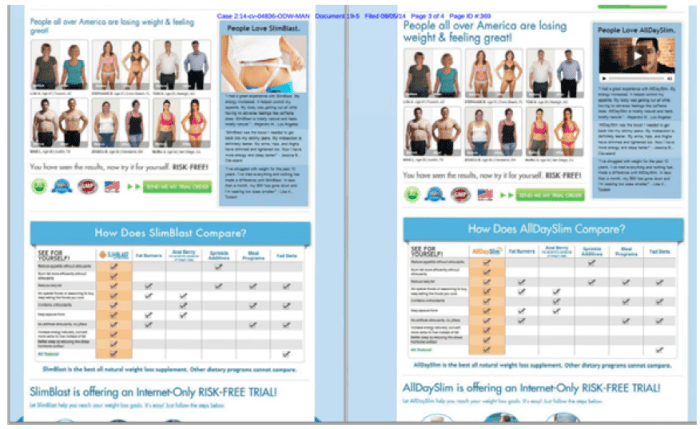

Lastly, the element of the likelihood of confusion has to be established. After defining the particular trade dress, the subject matter in hand is scrutinized to detect similarity with the allegedly infringing subject matter. Again, there is no microscopic dissection of elements; instead, the entire look and feel of both the websites, belonging to the plaintiff and the allegedly infringing one, are compared.

Concluding Remarks

The available technology to aid in copy-pasting of web content and the option of online templates to form websites have ushered more instances of uncalled replication of e-commerce websites and mobile phone applications. The same often leads to piggy-backing on a competitor’s reputation and goodwill while profiting from their work and making a place in the market.

The law on trade dress is nascent in most countries. Lack of specific laws and principles makes room for subjective analysis; therefore, no uniform guidelines can be formed to comprehend the fate of a website while seeking trade dress protection. However, until the law provides a straight jacket formula, the four-prong test laid above as deduced from the available judicial precedents can be utilized at this preliminary stage.