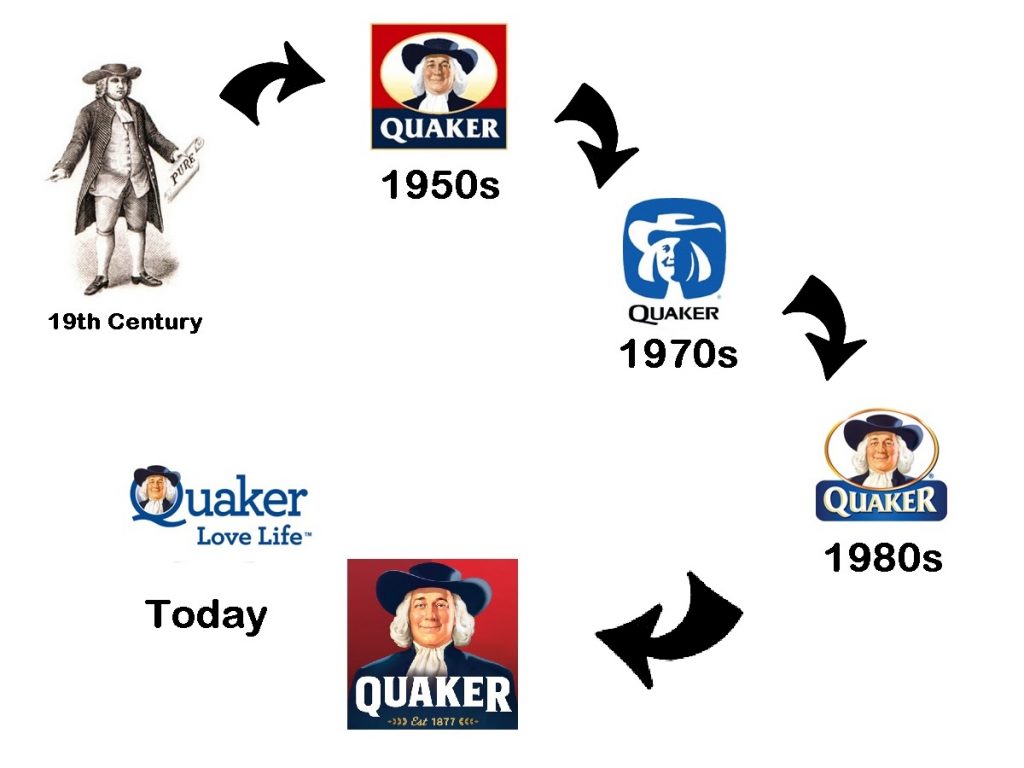

The Trademark Law confers the exclusive right to use a trademark up until it is maintained by the proprietor or an authorized user. Proprietors may choose to upgrade or introduce changes in their marks to meet the contemporary needs of the culture and society. However, it should be noted that any modification of the original mark has a significant bearing on the nature of rights exercised. It is where the Doctrine of Tacking in trademarks assumes the center stage to bridge the gap between an old mark and a refurbished mark.

The Concept of Trademark & Infringement: Extending Conventional Boundaries

A trademark is any word, name, symbol, or device that can be graphically represented to identify the origin of the goods and services and distinguish the goods and services of one from that of another. Therefore, as long as the mark is in commercial use, the trademark owner has the exclusive right to use his mark and prevent any subsequent owner from using any mark that bears similarity or identity to his mark, possibly leading to confusion amongst the masses. Where the intent to resume use is absent, the mark is considered abandoned and is returned to ‘public domain.’ By such virtue, marks of such nature are open for adoption by others to identify the source of their goods and services. Whether or not a mark has fallen in the public domain isn’t always objective but requires the consideration of many factors.

Contrary to this basic principle of strictly confining marks, as early as 1900, it was established that the rights over a trademark might extend beyond the precise form adopted and registered by a proprietor. For instance, in Saxlehner v. Eisner & Mendelson Co., the Court held that the rights over the registered mark ‘Hunyadi Janos’ for bottled water were inclusive over the right to use only the term ‘Hunyadi’ in seclusion since it was a ‘principle word’ of the mark, and hence, was not free for use by others. It was the start-point when courts began to address that the right of an owner is not confined only to the exact manifestation of the registered mark. Hereafter, courts began to assess the freedom of trademark owners to redecorate or re-ornament their original marks, as also witnessed in Beech-Nut Packing Co. v. P. Lorillard Co.

Rationale behind the Doctrine of Tacking

There aren’t many precedents to establish the exact parameters of the Doctrine of Tacking. Therefore, where a few countries may permit the original and altered variants of a trademark to co-exist, some still do not pursue this course.

The Doctrine is founded on the rationale to permit proprietors to retain the variants of their mark while they uphold the original commercial and consumer impression. In the absence of such a Doctrine, proprietors will be discouraged from making changes to their marks to prevent them from evolving aesthetically and utilizing new advertising and marketing styles that may be utilized by new entrants, placing the prior mentioned at a commercial disadvantage. The same is not to enable expansion and evergreening of both variants. In the case of Sengoku Works Ltd. v. RMC International, Ltd., 96 F.3d 1217, 1219 (9th Cir. 1996), the Court opined that the Doctrine helps the proprietor of an old mark to avail the same rights concerning the new mark while enabling the audience to identify the source of the mark and disabling the appropriation of both marks by competitors.

Let us take an example to simplify this. Suppose there is a chocolate manufacturing company using its registered mark ‘Choco-lattehh’ with the device of a panther for a couple of years. The company’s R&D department suggests modernizing the mark to increase and maintain its association only with a younger audience and use the mark ‘Choco-kiddy’ with the device of a panther. The question that arises is whether the proprietor loses the rights over the old mark only by reason that the mark has now been upgraded to a newer version? The answer lies in the next segment.

Where did this Doctrine Spring-up from: Tracing the Antecedents

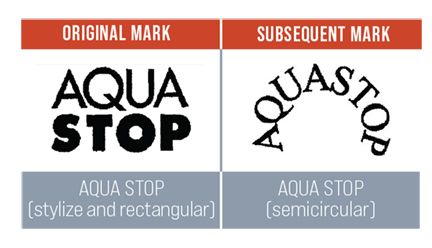

The issue of relying on an original form of a trademark while also utilizing an updated form of the trademark was addressed in the case of Jack Wolfson Ausrustung fur Draussen GmbH & Co. KgaA v. New Millennium Sports, S.L.U., 116 USPQ2d 1129 (Fed. Cir. 2015). In this case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) dealt with the issue at priority and held that only if an old form and the new form of the same mark are legal equivalents can tacking be permitted. In this case, the prior mark was ‘KELME,’ which was immaterially altered by utilizing a different font style while retaining the letters ‘KELME.’ In such scenarios, the Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (“TMEP”) §1212.04(b) should be referred which states that “A proposed mark is the ‘same mark’ as a previously registered mark for 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(1) if it is the ‘legal equivalent’ of such a mark. A mark is the legal equivalent of another mark if it creates the same, continuing commercial impression such that the consumer would consider both the marks to be the same.”

The element of ‘commercial impression’ requires the consideration of a wide variety of evidence like visual aspects, aural similarity, consumer surveys, etc. Therefore, it can be construed that the marks should not be materially different from one another, and the latter mark should imply the same commercial impression as that of the earlier mark. The courts also take the intention of each trademark owner into strict consideration.

The Doctrine of Tacking is deployed when there are three marks in question. Let us consider them MARK A, MARK B, and MARK C – Where MARK A and B belong to the same proprietor, MARK A being a prior mark and MARK B being a refurbished mark. MARK C, bearing similarity to MARK A, is being proposed for use by another party. Here, the proprietor utilizing the Doctrine of Tacking can exercise the right of priority over Mark C belonging to some other party since Mark A and Mark B are sufficiently similar. In this scenario, if continued use of the prior mark is established, it further strengthens the case of tacking over a trademark.

However, as held in Van Dyne-Crotty, Inc. v. Wear-Guard Corp., 926 F. 2d 1156, 1159, the Doctrine of Tacking is not often deployed and is utilized only for exceptionally narrow circumstances.

Concluding Remarks

Given all the points mentioned above, it is safe to say that trademark proprietors should exercise proper care while considering modifying or making any alterations to the mark. They must be acquainted with the recent developments of the law and how these doctrines are put to practice to ensure their attempt to seek an advantageous stance does not negatively impact the scope of the mark.