There has been a tilt-shift in understanding how Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) can be utilized in the best possible manner in the realm of computer programming. Is it by securing rights of exclusivity or opting for a different channel entirely? However, not everyone may be concerned about the aspect of commercialization; for instance, research scholars and academicians, per se; therefore, the answer to the question may vary.

Hence, there exist two opposing poles, namely, copyright and public domain; and somewhere in the middle lies open-source software. To rip the band-aid off, before we delve into the subject matter, let us understand that Copyleft, Open Source, and Public Domain are all different things, and therefore, not necessarily free or absolutely without restrictions.

Copyright vs. Copyleft in Software

Like all Intellectual Property (IP) laws, Copyright Law also prohibits unlawful use of the author’s rights, including the right of reproduction, adoption, or distribution of copies of their work. Therefore, where such private rights are to be exercised, it requires seeking permission through licenses or negotiating contracts. Consider an example of you having a music CD of Enrique’s album Euphoria. Since it is copyright-protected, you are prohibited from making its copies and circulating it amongst your friends.

On the contrary, copyleft operates on the notion of the utmost freedom. The idea was incepted by Don Hopkins and gained popularity later in the 1980s because of Richard Stallman. It gives the user the right to utilize software and make additions or modifications using it to create a ‘derivative’ work. This piece of derivate work is also governed by the same license as that of the fundamental software, which means that the user of copyleft license cannot add any terms to the derivative or downstream software for introducing restrictive rights in his or her favor. In simple words, you can use the software under a copyleft license to make your version; however, it has to give users of such modified software the same rights and freedoms as you may have had while developing it.

While using such copyleft licenses, one may be inclined to use the mirrored ‘C’ in a circle instead of an actual copyright symbol. Such legal mistakes should be avoided since copyleft is legally based on copyright, and hence, the derivative shall also have a notice of copyright attached to it. It is interesting to note that although the aspect of copyleft licenses is much popular in the software industry, the same license can be used upon other domains as well. An example of this is the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license, which is used for creative works like literature, art, etc.

While using such copyleft licenses, one may be inclined to use the mirrored ‘C’ in a circle instead of an actual copyright symbol. Such legal mistakes should be avoided since copyleft is legally based on copyright, and hence, the derivative shall also have a notice of copyright attached to it. It is interesting to note that although the aspect of copyleft licenses is much popular in the software industry, the same license can be used upon other domains as well. An example of this is the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license, which is used for creative works like literature, art, etc.

Copyleft vs. Open Source Software (OSS)

These two terms are often confused with one another. However, Copyleft and Permissive licenses are a subset of Open Source Software. Open Source Software gives more extensive rights to the user for making use of the source code to introduce modifications or alterations, which results in an improved product code. The product code does not have to abide by the same license from which it had emerged, and thus, it can be commercialized without needing to publish it or share it in the open. In one such case in the EU, namely, Jacobsen vs. Katzer, Jacobsen used to manage the OSS, while Katzer used to develop commercial software, Decoder Commander. The said developer failed to comply with the Artistic requirement of attribution, which led to a suit of Copyright Infringement. The Appellate court sided with the plaintiff and stated that “if a license is limited in its scope and the licensee acts outside the scope, the licensor can bring an action for copyright infringement.” Whereas, for copyleft, as observed above, the product code is governed by the same license by using which the software came into being. Hence, it cannot be armed with additional rights or restrictions.

These two terms are often confused with one another. However, Copyleft and Permissive licenses are a subset of Open Source Software. Open Source Software gives more extensive rights to the user for making use of the source code to introduce modifications or alterations, which results in an improved product code. The product code does not have to abide by the same license from which it had emerged, and thus, it can be commercialized without needing to publish it or share it in the open. In one such case in the EU, namely, Jacobsen vs. Katzer, Jacobsen used to manage the OSS, while Katzer used to develop commercial software, Decoder Commander. The said developer failed to comply with the Artistic requirement of attribution, which led to a suit of Copyright Infringement. The Appellate court sided with the plaintiff and stated that “if a license is limited in its scope and the licensee acts outside the scope, the licensor can bring an action for copyright infringement.” Whereas, for copyleft, as observed above, the product code is governed by the same license by using which the software came into being. Hence, it cannot be armed with additional rights or restrictions.

Some widely-known examples of Copyleft Software are as follows:

• VLC media player

• 7-Zip

• Firefox

• Openoffice

Speaking of OSS, there is no explicit mention of its recognition in the Indian statutes, neither in the IT Act, 2002, nor the Copyrights Act nor the Indian Patent Act, 1970. However, section 29(o) of the Indian Copyright Act of 1957 recognizes ‘computer programs’ as inclusive of literary works. Section 14 throws light on the rights of the owner of a computer program, which includes the right “to issue copies of the work to the public not being copies already in circulation.” Following the said provisions, open source may be inclusive of the Copyrights Act. Also, since the copyleft license is a subset of OSS, where OSS is allowed, there is scope for protection of copyleft licenses as well.

Similarly, in the UK as well, the Cabinet Office has officially adopted an Open Source Strategy to remove the absolute reliance on IT suppliers and enhance the value for money. A few companies who have embraced this policy are Canonical, Tyk, Sirius, Seldon, etc. Furthermore, the US has also acted in such a favor. Earlier in 2016, the government had announced a new federal source-code policy wherein 20% of the source code, which is developed by or for any agency of the government, will be released as an OSS on code.gov. However, the policy has not been utilized to its full potential since very few agencies have complied with it. Thus, it wouldn’t be wrong to conclude that OSS is much prevalent in the private sector.

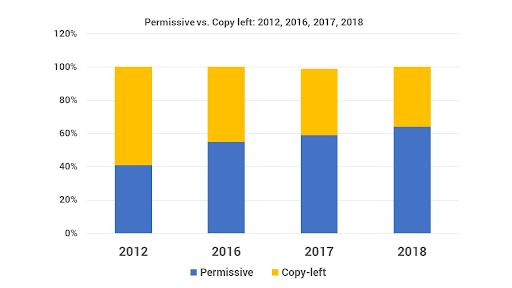

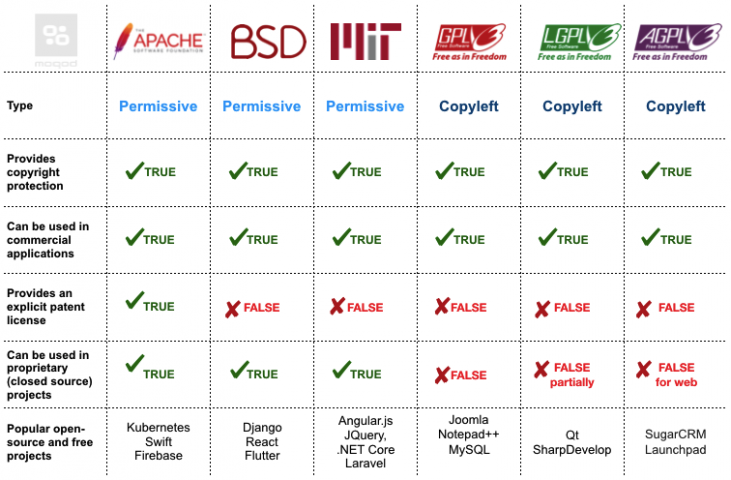

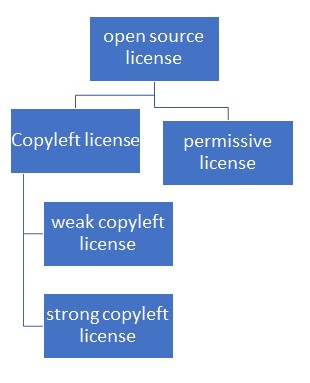

Types of Copyleft Licenses

Open source licenses can be either permissive or be copyleft licenses. The only difference is that copyleft licenses are persistent since the same license applies to all the works that are a result of it. On the other hand, permissive licenses are not persistent. Also, copyleft carries a ‘viral effect,’ which means that when a derivative work is made by using two different licenses, out of which one is copyleft, the derivative work is governed automatically under the terms of the copyleft license. The same doesn’t hold for permissive licenses. It shows us the two capabilities of copyleft licenses – firstly, they are ‘persistent,’ and secondly, they have a ‘viral effect.’

There are majorly two types of copyleft licenses. Let us look at each one of these to understand the concepts in depth.

-

- Strong Copyleft License – Where the copyleft license does not mention whether it is strong or weak – it is assumed that it is a strong copyleft license. Only strong copyleft licenses have a viral effect; for instance, GPL (General Public License), AGPL (Affero General Public License).

- Weak Copyleft License – It can be used while utilizing the source code governed by another license as well, and hence may result in constituting ‘aggregate works;’ for instance, LGPL (Lesser General Public License), MPL (Mozilla Public License).

Advantages and Disadvantages of Choosing a Copyleft License

| S. No. | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|

1. |

Usually, it is free of charges. If any consultation fee is charged, it is generally less. | There may be an additional cost of using plugin modules or other such necessities. |

|

2. |

There is a right to work on the parent software as per consumer needs. | The modified software cannot be used to seek an exclusive right for commercial exploitation. |

|

3. |

The derivate work can be used by the modifier without incurring a greater cost. | It may not always incentivize labor or promote innovation. |

|

4. |

No middle-man is involved. Cost or vendor fee is required to be paid. | The terms of use of such licenses are often very complicated and can have extensive repercussions, which may not always favor the modifier’s stance. |

|

5. |

It promotes a better environment built on cooperation and collaboration. | It proliferates a forced idea of community-creation for using resources therein. |

|

6. |

It promotes a culture of efficiency and improvement. | There is a chance of conflict among the actual developer of source code, the modifier, the future developers of the modified version, etc. Too many parties may mean too many conflicts. |

|

7. |

It is easy to update and modify without seeking additional permissions, licenses, etc. | To control malice and unfettered use can pose an issue. |

|

8. |

Debugging is also comparatively convenient. | |

|

9. |

The support of the community can help raise and sort issues within the system. | |

|

10. |

It has limited scalability. |

Why should you Choose Copyleft Software License?

As has been noted above, the use of copyleft software license comes with many added benefits. A developer should consider such a license when he is working on a small project, which may not need many developers to study such programming, and how it can be used to extract maximum benefit. It also generates a culture of ‘give back’ to the public for the community to benefit from it. Take the example of the GNU project. It aims to give all users the freedom to make changes to the GNU software and then distribute the same to the community directly by eradicating any middlemen. Such programs are ideal for Universities and Companies; however, majorly depending on the nature of the action being pursued. Also, it is important to note that as per the precedent set by the Federal Court (US) (although the developer of modified work has to contribute to the community), the community does not have the right to move to court to enforce such a license. In the Versata case, the third-party beneficiary had no standing under the copyright law.

But, as also observed above, there is no option of not giving back after availing of the service. This was also witnessed in the CoKinetic’s lawsuit against Panasonics for utilizing a Linux-based operating system conditioned on free distribution of the source code. Panasonic refused to distribute the same to block all competitors, including the Plaintiff, which led to infringement of the license.

However, before opting for a copyleft software license, the developer should consider the following aspects:

- User & Developer Documentation: This is the basic foundation of your decision-making. While considering the use of an OSS or copyleft licensed software, the legal terms and expressions should be clear, if not simple. The direction of usage should be explicit for each kind of right availed.

- Security-Based Provisions

- Type of License: The terms of an agreement can show whether the OSS is permissive or copyleft in nature. If it is embracive of copyleft, it is crucial to determine whether it is a weak or a strong copyleft license. The same should be checked before making any use of licensed software; else, one may be caught up in unnecessary and costly litigation.

- Support Services: The quality of support is crucial in determining the quality of the software as well, which may be beneficial in the later time to come. Both types of support – community and paid, provided alongside one another, are a good indication.

Conclusion

The idea of copyleft has culminated from the varied use of the copyright law itself. It enhances the outlook of copyright by securing freedom and liberty to operate, use, modify, and also distribute such software programs. The same is contrasting to the traditional notions of copyright. However, it seeks to enhance communal creativity by creating a sense of multiple ownerships. The concept is still growing, and therefore, some organizations may find it very challenging to understand and adapt to it. To keep track of such use contrary to licensing terms is also another component of added difficulty.

Thus, it is imperative that before such a choice of opting for a copyleft license is taken, the concept of public domain and copyleft licenses under open source licensing should not be confused with as it may have serious legal repercussions. In this globalized and digital world, copyleft can procure better results, and therefore, to count OSS/copyleft licenses as an option in the world of computer programming is nothing but a very prospective option.