Remixes and remade versions of songs and music pieces have become a common affair in all music and movie industries alike. A remix is a piece of media, which has been modified, altered, or contorted from its original version by either adding, removing, or changing the original version. The term can be used for a song, artwork, a book, video, poem, or even a photograph, but here, the reference is to music. It has been observed that most of the cultures around the world have developed and evolved through the mashing up of different cultures. Consider the arts and architecture of Renaissance Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, which are directly derived from Ancient Rome and Ancient Greece. Similarly, the Panchatantra is an ancient collection of Indian animal fables arranged in the format of a story, which was composed way back in 3 BCE, and over the years, it has been recreated in almost 50 different languages all around the world.

Earlier times witnessed the assimilation of cultures in a different paradigm but what we see today is due to a heavy influence of rapidly changing technology and the application of computer software to embody cultural expression. Access to such technology has also made wide dissemination possible. Therefore, everybody and anybody who has access to a stable internet connection and a computer can create remixes, mash-ups, and spin-offs by simply combining musical and audio-visual elements to create new works.

Addressing Copyright amidst Remix Culture

The question of remixes being governed under copyright is not explicitly dealt with in most of the national Copyright Laws. Therefore, there is a lot of ambiguity surfacing around the issue, including whether remixes are legal or illegal, whether they need to qualify the essentials of copyright in addition to other features, or should they be governed as per the rules laid for derivative works as enshrined under Article 2(3) of the Berne Convention on the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works.

Remixes as a Violation of Copyright Laws

As a matter of common belief, it is held that an unauthorized excerpt taken from an already existent work embodied in another work constitutes Copyright Infringement. It is so because the secondary work (remix) is violative of the original author’s exclusive right of reproduction as also found in Article 9 of the Berne Convention in addition to his right to communicate the work to the public as found in Article 8 of the WIPO Copyright Treaty. The question of moral rights also comes into the picture since the right of integrity against any distortion, mutilation, or modification sides with the author as also laid under Art 6bis of the Berne Convention.

Remixes as being Compliant with Copyright Law

Whereat one stance, it might seem like a violation; at the other, it can be observed to comply with the copyright laws. Article 13 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) lays down that an exception can be made in “certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.” It means – for refraining from normal exploitation of the work, no commercial use or gain shall be derived from it since personal use does not threaten the original authors’ exclusive rights of exploitation.

The secondary work may also be protected as constituting a quotation, which is governed under Article 10 of the Berne Convention. It states that “it shall be permissible to make quotations from a work, which has already been lawfully made available to the public, provided that their making is compatible with fair practice, and their extent does not exceed what is justified by the purpose.” These quotation works are not limited to just literary works but also include audio-visual, musical works, and photographic works.

Jurisdiction Specific Analysis

a) Canada

Canada has specifically dealt with non-commercial user-generated content in its Copyright Modernization Act 2012 in article 29 stating that an act does not amount to infringement if:

- The work is used solely for a non-commercial purpose;

- The source of the work is mentioned;

- The individual has reasonable grounds to believe that he or she is not infringing copyright; and

- The remix does not have a ‘substantial adverse effect’ on the exploitation of the existing work.

b) The United States

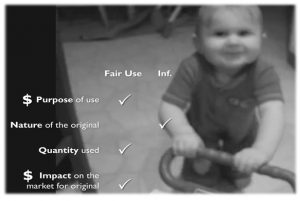

The equation is not very clear when it comes to the US. The matter is, therefore, left with the courts to decide, as was also witnessed in Stephanie Lenz vs. Universal Music Corporation. In the said case, Stephanie uploaded a video on YouTube of her children dancing in the kitchen while Prince’s ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ was playing in the background. The same was removed at the request of Universal Music Corporation for alleged Copyright Infringement. The District Court ruled in favor of Stephanie while stating that copyright owners do not have the authority to take down content before undertaking a legal analysis to determine whether the remixed work would fall under the doctrine of fair use or not, which is a concept in the US copyright law that permits limited use of copyrighted material without the need to obtain the rights holder’s permission. Thus, the question of copyright is at the mercy of the courts.

c) India

In India’s copyright legislation, section 52(1)(j) governs the domain of authorized copying while making remixes or remakes of sound recordings. It states that an act would not amount to infringement if there exists a sound recording of the original literary or musical work and the person who wishes to copy the same has given due notice of his intention to use it to make a sound recording. In addition to the same, the second user has to pay the original owner the royalty price that has been fixed by the Copyright Board. Furthermore, the new sound recording should not be marketed with labels or packaging that might mislead the public about the identity of the artist with a mala fide intent. Lastly, the remix should not be made until the expiration of two years after the end of the year in which the original song was made.

d) The European Union

In the EU, the discussion on remixes is at a bare minimum. However, it is abundantly clear from article 2 and 3 of the Copyright Directive that the right of communication of the work to the public as well as the right to make the said work available in favor of the author of the work. Therefore, remixes are a prima facie infringement of these rights. At the same time, there is no explicit copyright exception provided for in the European Union that allows the use of the copyright-protected works to be used to produce user-generated content. It means that remixes, whether in terms of commercial use or non-commercial use, are not permitted. Also, many states within the EU do not provide an exception of parody, so the exception of comic-reproduction is also ruled out from the defense against a probable infringement. Therefore, the law in the EU does not exist in harmony with the latest technical developments addressing user-generated content separately or within the said Directive as well, which is capable of creating cross border issues and undermining the social acceptance of copyright as a whole.

Check-List for Creating Remixes

Therefore, on such accord to make legally authorized remix music, the composer should keep in mind the following checkpoints:

- Always consider purchasing authentic music albums. Making remixes from pirated music CDs or through unauthorized downloading is not the preferred route.

- Attribution is the right of the proprietor of original music. Therefore, before using anyone’s music recording, consider obtaining prior permission. However, amateurs who want to remix music for their personal use may not need to seek permission.

- Also, it is preferable to wait for at least two years before recording the remix incorporating the original music.

- It is preferable to make a record of the permission gained.

Conclusion

In today’s times, remixes can be perceived as a separate genre of music in the digital age, deserving the same protection as other types of works. There is a lot of ambiguity about the law addressing the issue of remixes and whether they infringe upon the rights of the original author of the work or not. Specifically speaking of the US and the EU, neither of the legal systems offers certainty. It is time that policy-makers indulge in decision-making to take a new look at copyright to give space to remixes and remakes, as also observed in a Green Paper issued by the US Department of Commerce Internet Policy Task Force. The relevant laws should address and cater to the needs of both the owner of the original work while striking a balance against the use of such content to recognize the importance of technology and provide a solution accordingly. It could include the introduction of a statutory licensing system or even fixation of royalty rates, etc.