30-05-2022

Category

Archives

30-05-2022

23-05-2022

23-05-2022

16-05-2022

16-05-2022

09-05-2022

The repurposing of drugs to find immediate solutions for new diseases is witnessed commonly in the pharmaceutical sector. In recent times, the same is instead a frequent instance to treat flues and viruses, as also perceived while identifying the solution for the Big-C, the ‘Coronavirus.’ The antivirals used to cater to diseases like HIV and SARS were clinically tested to adjudge their efficacy in the fight against COVID-19. Remdesivir, which was earlier utilized for the treatment of Ebola, is now used as a dose of Coronavirus vaccine. Similarly, acetylsalicylic acid, often known as Aspirin, was developed by Bayer in the year 1897 to treat pain and fever. However, it is now also utilized as an effective cardiovascular medicine that decreases the chances of suffering a heart attack or stroke. While the Patent Law safeguards the exclusive rights of an invention’s proprietor up until a specific specified period, it also protects new uses of known drugs. Let us find out how.

Can a Patent be Sought for Second Medical Use Claims?

When a substance or composition is already known for primary medical use, it may still be safeguarded as a patent for a second or subsequent medical use; however, the proprietor must prove that such use is novel and inventive. Furthermore, such patents should be meticulously drafted and litigated.

There are several instances where existing medicines are being developed for new medical uses. Consider the following examples:

- Sildenafil citrate, which is primarily used for heart and vascular diseases, came to be later marketed as a drug for erectile dysfunction.

- Finasteride, primarily meant for the treatment of prostate disorders, was at a later stage found to be effective in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia.

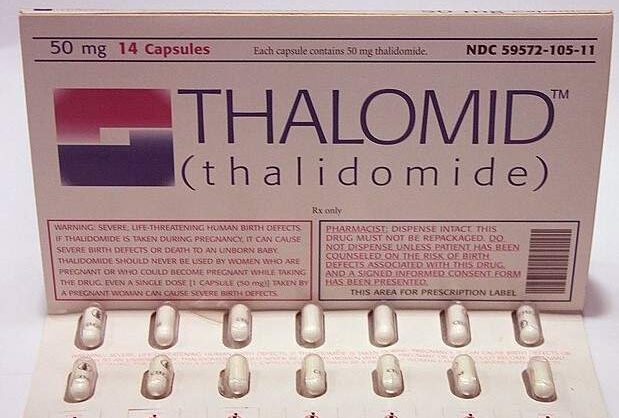

- Thalidomide was patented for respiratory infections; however, its second use was found to help relieve morning sickness in pregnant women. Also, it was discovered to be useful in the treatment of diseases like leprosy and cancer.

The European Stance on Second Medical Use Claims

Second medical use claims were not permitted until a fairly long period in Europe. However, after 1984’s landmark G5/83 decision, second medical use claims began to be acted provided they were written in the ‘Swiss-type’ format depicting:

“Use of Compound X for the manufacture of a medicament for use in the treatment of Disease Y.”

This legal trend of the Swiss-type format was then substituted by the “purpose-related product claims” since it became the new mandate after the EPO Enlarged Board appealed the landmark G2/08 decision. A purpose-related product claim should be in the format depicting:

“Product X for use in the treatment of Disease Y.”

The second medical use patent may address the following concerns:

- The use of a known drug to treat a new disease (“Known drug/new disease”)

In most patent claims, the phrase “for use” is interpreted as “suitable for use.” However, second medical use claims are an exception to this generality and are fully use-limited product claims. They can be used for the treatment of multiple diseases by covering them in a single claim, but the treatment of all such diseases must form a single general inventive concept as stipulated under Art. 82 EPC.

- The use of a known drug to treat a known disease using a new therapeutic method (“Known drug/known disease/new therapeutic use”)

A second medical use claim can also be filed for the treatment of the very same disease in the form of providing a new therapeutic method in the form of a new dosage regime, administration mode, or patient group, as also provided under G2/08.

Issues Surfacing Second Medical Use Claims

Lord Justice Floyd once said, “Whilst it is widely recognized that there are valuable, sometimes life-saving inventions, which are made through the discovery of the new use of a known drug, their protection in patent law is problematic.” Let us look into these problematic concerns.

The main reason for claiming a second medical use patent is to prevent third parties and competitors in the market from infringing upon the proprietary rights of the inventor. However, generic drug manufacturers are often seen flouting the laws to seek commercial gains. To prevent such acts of infringement, it is a settled law that purposeful arrangement should be proven. The purposeful arrangement can be understood as a form of use wherein there is a recommendation in the form of a packaging insert, labels, or on medical information slips or prescriptions, which are distributed along with the drug.

Also, it is considered infringement only if the generic manufacturer intends to use the second medical use claims for the treatment of the patented indication, proving which is undoubtedly an uphill battle. Therefore, generic manufacturers adopt the following measures to prevent being trapped in a series of endless litigations:

- Using “skinny labels” by carving the patented indication from the medical leaflet, which comes along with the medicine;

- “In-label use” – the use in an indication that is mentioned only generically on the label and not in the specific form that is patented; or

- “Off label-use” – the use in an indication for which the drug has not received regulatory approval.

Furthermore, the problem heightens when we look at certain jurisdictions that do not offer any protection to second medical use claims. It includes countries like those in Latin America. Even mass producers of generic medicines like India do not afford any rigid and concrete protection against such patents.

Conclusion

It should be understood that inventions in the domain of pharmaceuticals involve great capital expenses and abundant research and development initiatives. Bringing a new molecule itself does not cost any less than one billion, and therefore, this time-consuming process is cushioned if second medical use patents are safeguarded. It is a relatively cheaper route; however, qualifying clinical trials of all stages is yet another elaborate affair. Therefore, laws should address the infringement issue of second medical use patents to protect these claims adequately while also keeping misuse like doubt patenting and illicit activities under check. It shall be interesting to observe how lawmakers juggle around this issue to afford better and affordable protection.

02-05-2022