Introduction

Knowledge is the powerhouse of every growing industry. Such knowledge could be based on extensive and costly research from private R&D endeavors or even through indigenous communities in the form of Traditional Knowledge (TK). Indigenous and local communities (ILCs) often rely on biological resources for everyday activities, which are of utmost importance to bio-prospectors or users of genetic resources to utilize the potential of flora and fauna. Therefore, traditional knowledge has more significance than imagined due to which the issue of benefit-sharing has gained the spotlight.

What is Traditional Knowledge?

The internationally accepted definition of TK is still unclear, probably, because it does not find clarity within the most integral and fundamental agreement on Intellectual Property (IP), the TRIPS Agreement (Art 27.3(b)). However, the meaning of TK is as clear as its name itself. It stands for the know-how, experience, expertise, and the application of knowledge, which was established in earlier times and was passed on from one generation to the next within a defined locality, region, or community due to continuous performance. This continuous practice of ‘living-knowledge’ becomes essential to the cultural identity of the designated group of people for the peculiarity of such practice. It is not limited to agricultural or ecological practices but also extends to literature & art, scientific, biodiversity, technical, and medicinal based knowledge as well. Since they are usually not documented and acquired by information spread through word of mouth, there are a lot of issues that surface in the domain of TK.

Let us have a look at some valuable and well-known forms of TK all around the world:-

| S. No. | Traditional Knowledge (TK) | Country/Area/Locality |

|

1 |

Tea | It was traced in Ancient China when Shen Nung discovered it in 2737 BC. |

| 2 | Chewing-gum | It was traced as TK since Pre-Columbian Mayans extracted gum from the sapodilla tree found in Mexico and Central America. |

| 3 | Surfing | It was a technique practiced by fishermen in Western Polynesia to catch fish easily. |

| 4 | Anesthetics | It was used by local anesthetics in ancient Incas around 1000 AD. |

| 5 | Football | It was played in China first during 2-3 BC. Even Japan developed its version of football known as Kemari. |

| 6 | Popcorn | It is said to have originated in the Bat Cave of New Mexico in 1948. |

| 7 | Ashwagandha | Also known as ‘Withania Somnifera,’ it is used to treat heart ailments and was first used in India. |

Approaches to Traditional Knowledge (TK)

There are two general ways of approaching TK as such. The first and the most conservative approach is the ‘Defensive Mechanism,’ which helps to adopt strategies to ensure that third parties do not receive any illegitimate rights over their TK. This approach is also adopted by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in the form of the WIPO-Classification System and disclosure requirements, which allow the applicants to submit data on how they arrived at an invention that is novel and has an inventive step. Many countries have their TK database to protect the TK by documentation. The second approach, ‘Positive Protection,’ is by preventing the unauthorized use of TK but at the same time, exploiting it to secure the maximum benefit to the original community itself. So, under which approach does benefit-sharing fall?

Understanding the Term ‘Benefit-Sharing’

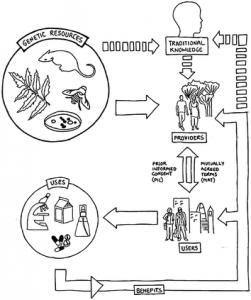

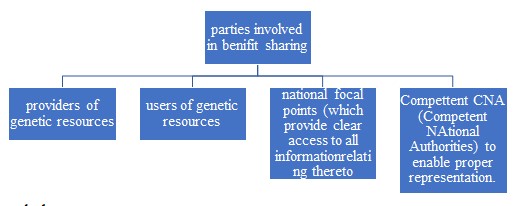

Before we answer the question stated above, we need to uncover the meaning of benefit-sharing and why is there such hustle-bustle around it. As mentioned above, TK reflects a unique set of indigenous forms of knowledge, which often has very precious values attached. Earlier due to exploitation and colonialism and later due to globalization, the meeting of different cultures and adoption of ‘western’ techniques, these practices have often faced the threat of being eroded. Therefore, the role of IP is seen as to safeguard this form of knowledge. The same is also seen as exploitative by some, but that is another discussion altogether. Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) is the many ways by which genetic resources may be approached and utilized for the greater good. It simply connotes the mechanism of accessing and utilizing genetic resources to deliver benefits to the users and providers. Therefore, it counts as ‘Positive Protection’ since it authorizes active exploitation of TK but with a certain degree of control and authorization.

The Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) recognized the role of TK by promoting its extensive application in general but with prior approval (also known as PIC- prior informed consent) and involvement of the righteous owners of the TK through MAT (Mutually Agreed Terms). It requires the sharing of such knowledge for the benefit of humanity in general, which means the society, the public sector (government), the private sector (including research organizations), and, most importantly, the proprietors of such knowledge

The idea of access and benefit-sharing seems very novel; however, there are a lot of issues that need to be addressed for fully utilizing benefit-sharing. Some of the key issues are mentioned below:

- Since TK is held collectively, it becomes arduous to identify exclusive proprietors. Lack of documentation makes this even more difficult.

- When negotiating on benefit-sharing, since there is no single proprietor, the needs of the entire community are to be taken into consideration instead of a personal-rewarding system.

- Once this sharing is negotiated, the absolute ownership rights are somewhat added to ‘stewardship duties or obligations’ since all rights are followed by some duties.

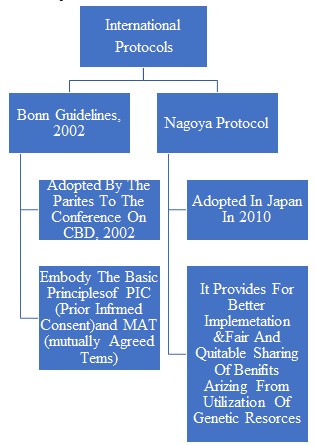

International Protocols/Guidelines on TK and Benefit-Sharing

The ‘Bonn Guidelines’ were the first guidelines adopted at an international level to ensure that countries implement Access and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) mechanisms carefully and effectively. These guidelines emphasized countries to have their national approach suitable to their jurisdiction for ABS, especially about the PIC requirement, and to negotiate MAT based contracts/ agreements to the benefit of both user and provider.

The ‘Nagoya Protocol’ was a more defined approach to the issue, which came to be enforced in 2012. It specified parties to take measures corresponding to:

- Access Obligation: It focused on the adoption of clear, specific, non-arbitrary, and fair rules and procedures for PIC and MAT

- Benefit-Sharing Obligation: It stated that benefit-sharing at the domestic-level shall be afforded. The benefits of emanating can be monetary or non-monetary.

- Compliance Obligations: It stated that the domestic legislation of the provider’s jurisdiction shall be followed in terms of matters relating to compliance.

What to Ensure While Pursuing the ‘Benefit-Sharing Approach’?

The following should be considered while taking the approach:-

- The exploitation of indigenous parties should be avoided at all costs. Rather, such benefit-sharing should aim at contributing to the strength and development of all parties by ensuring that there is equitable access to information, effective and active participation, as well as access to the improvements made to the TK, if any, to all stakeholders equally. For instance, Bio India Biologicals exported neem leaf from Andhra Pradesh, India, for 0.053 million, in return for benefit-sharing.

- Similarly, the exploitation of resources should be avoided at all costs, which implies that a sustainable approach should be taken in line with the objectives of CBD (Convention on Biodiversity).

- The commercialization or utilization of knowledge arising from benefit-sharing should not intervene with the indigenous use or practice of such knowledge to prevent the providers from exercising their legitimate rights.

- There should be an observance of mutual respect while dealing with the diverse cultures and people from such cultures without undermining basic human rights.

- The process and the agreement between the parties should not be ambiguous. The process should be transparent and understandable to enable parties to make the right and informed choice.

- The terms of such sharing should identify the rights and duties of each party, and the source of origin of such resources should be identified therein to prevent misappropriation of such TK.

Examples of Successfully Enforced ABS Agreement

- Africa is home to many traditional forms of art and practices emanating from knowledge gathered over hundreds of years. A few examples could be the high-yielding Zimbabwean developed variety of SR52 Hybrid maize, Neem Biopesticides in Togo and Niger, and the Ethno- Veterinary Medicine from the Niger River.

The Nagoya Protocol has specifically improved the Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) due to its legally binding nature. One of the best examples witnessed in the domain of ABS was recently observed in the Rooibos Benefit-Sharing Agreement (RBSA) in South Africa, which utilized the framework within the contract law and NEMBA Act (National Environmental Management Act). Rooibos can be used for a wide array of products in the form of tea, cosmetics, novel foods, flavorings, etc. The Agreement recognized the San and Khoi people as the holders of TK. The RBSA incorporates provisions enabling respect, honesty, fairness, and care in the Agreement.

The Nagoya Protocol has specifically improved the Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) due to its legally binding nature. One of the best examples witnessed in the domain of ABS was recently observed in the Rooibos Benefit-Sharing Agreement (RBSA) in South Africa, which utilized the framework within the contract law and NEMBA Act (National Environmental Management Act). Rooibos can be used for a wide array of products in the form of tea, cosmetics, novel foods, flavorings, etc. The Agreement recognized the San and Khoi people as the holders of TK. The RBSA incorporates provisions enabling respect, honesty, fairness, and care in the Agreement. - PepsiCo negotiated an ABS Agreement with a fisherman community rooted in Tamil Nadu, India, for their traditionally grown and harvested seaweed, the 2000 MT seaweed, which it exports to Malaysia, Philippines, and Indonesia. The Agreement paid royalty at 5% of FoB (Free on Board), which equals Rs. 3.9 million.

- An ABS Agreement came into being between the San people and the CSIR (Council for Scientific and Industrial Research) for using active compounds of the Hoodia plant. The Agreement laid down certain monetary and non-monetary benefits, including funds for the development, education, and vocational training of the San Community.

Such examples can help build faith in benefit-sharing to negotiate a win-win deal built on genuine benefit and strong legal support.

Conclusive Remarks

As observed above, there are many such products out in the market that we wouldn’t have known about if indigenous knowledge was not given its due importance, which includes coffee, rubber, syringes, etc. In terms of bio-resources, such unraveling TK is even more crucial since it may lead to medicinal or therapeutic discoveries. The same stands correct for most of the communities rooted in South Africa and South Asia. Even though there are international protocols and agreements, the regulation at domestic levels is still incomplete due to which the stakeholders may still be skeptical of utilizing the ABS mechanism.

In addition to the protections afforded under CBD and other international instruments, national initiatives are crucial to ensure the sustainability and existence of such cultures in these communities. Before taking other steps, having an inventory or library of proper recordation of such TK and the respective communities they belong to is very important. Also, legislative steps, along with the administrative extension of services, are a must to utilize these resources but with equitable benefits ensuing back to the community. A proper ABS will help disseminate such valuable knowledge through legitimate use and help improve the quality of life of those making use of it. Also, the providers will benefit from better procurement prices through royalty sharing.

Therefore, to summarize the requisite steps to be taken in the direction of the promotion and protection of TK, the following aspects should be considered:

- Equitable incentivization to the providers

- Defining government policy for access and benefit-sharing

- Introducing proportional royalty rates

- Increasing the awareness of locals/communities about traditional knowledge